Insurance, the Rothschilds, and Indian Bond Markets

Personal finance, investment philosophies and fun facts - all without the jargon.

Welcome to the fourth edition of the Bodhi Newsletter! In today’s edition, we cover:

Types of Insurance: Whole Life and Term Life

The Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waterloo Fortune

Investor Spotlight: Chandrakant Sampat

Fundamental Analysis 101: EBITDA

An Explainer on Indian Bond Markets

Personal Finance

Life Insurance or Term Insurance? A Brief Explainer

By Krishna Dixit

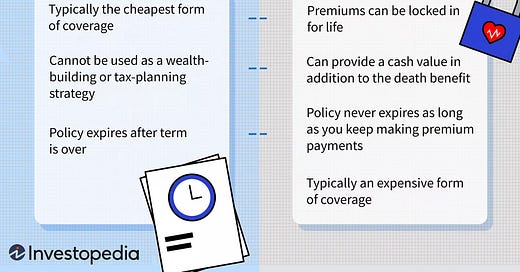

Life insurance serves as a crucial financial tool, offering a safety net for your loved ones in the event of your demise. There are two primary types – whole life and term life insurance, each with distinct features and benefits.

Whole life insurance is a form of permanent coverage, persisting as long as you continue paying premiums. It includes a cash value savings component – a portion of each premium payment is allocated to the cost of insurance and the rest is deposited into a ‘cash value’ account. This amount earns interest, and taxes are deferred on the accumulated earnings. As premiums are paid and interest accrues, the cash value builds over time, which you can withdraw or borrow against.

On the other hand, term life insurance is temporary, lasting for a specified number of years (the ‘term’) without accumulating any cash value.

Reputable life insurance companies offer both term and whole life options. Understanding the distinctions between them is crucial for making an informed decision.

One key aspect is the premium — term plans often come with lower premiums as the entire amount is directed towards insurance coverage. Whole life plans, however, allocate part of the premium for coverage and the rest for investment, contributing to the cash value component.

The tenure of the coverage is another differentiator. Term plans offer coverage for a fixed duration, ranging from 5 to 30 years. In contrast, whole life insurance plans come with flexible tenures, typically extending until the policyholder reaches 100 years of age.

Both life insurance and term insurance policies have their own benefits and drawbacks. On one hand, whole life insurance plans provide lifetime coverage, flexible premium payment terms, assured maturity benefits, flexible income payout options at a higher premium cost. On the other hand, term plan is a pure life cover which offers only death benefit at a very lost cost and affordable premium range.

For many, life insurance is more than a financial product — it's a strategic investment that continues to provide even after premium payments cease. Whether viewed as a safeguard or an investment, it plays a pivotal role in providing peace of mind and security during times of crisis and is considered an essential financial investment.

The Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waterloo Fortune

By Rishika Jain

The words of German philosopher Heinrich Heine, "Money is the god of our time, and Rothschild is his prophet," succinctly capture the influence of the Rothschild family in the world of finance. While presently their legacy endures through the persistent dominance of Rothschild & Co, a leading multinational financial advisory and asset management firm, their rise from humble beginnings in the Frankfurt ghetto to their role in Napoleonic Wars is a story that warrants more attention.

Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812) rose to prominence as the banker to Prince William of Prussia. When Napoleon's forces invaded Prussia, the Prince sought to safeguard his wealth. He entrusted his funds to Mayer Amschel's son, the young Nathan Rothschild, who was then working as a banker in London. Amid the Napoleonic Wars, Nathan Rothschild invested the Prince's money by supporting the British war effort against Napoleon. He became involved in smuggling funds to the Duke of Wellington's forces in Spain.

You might have heard the story of his infamous exploit at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 – how he spread false information by claiming the British had lost the battle and subsequently profited off the crash in stock prices at the London Stock Exchange. However, there is little truth to this story. Journalism professor Brian Cathcart traced the first widespread conspiracy theory to a political pamphlet called Histoire édifante et curieuse de Rothschild Ier, roi des juifs, which began rolling off European printing presses in 1846. Its most famous passage details Nathan Rothschild’s involvement in the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815. It claims that Rothschild was rushed to the Belgian coast and paid a fortune to cross the English Channel during a thunderstorm. He arrived in London 24 hours before the official news announcement of Napoleon’s defeat. The pamphlet further goes on to claim that as a result of this, he ‘suddenly won 20 million francs’ and the total profit made in the year totalled 135 million.

Cathcart’s investigation found that on June 18, 1815, Nathan Rothschild was nowhere near Waterloo. There were no reports of a storm over the English Channel at that time. And while the Rothschilds did profit immensely off the war effort against Napoleon, they did not make millions from announcing the Allied victory at Waterloo.

In fact, the real reason behind their profit is a lot more ingenious. Nathan Rothschild calculated that the future reduction in government borrowing brought about by the peace would lower yields after a two-year stabilisation. Nathan immediately bought up the government bond market, for what at the time seemed an excessively high price, before waiting two years, then selling the bonds on the crest of a short bounce in the market in 1817 for a 40% profit. Given the sheer power of leverage the Rothschild family had at their disposal, this profit was an enormous sum.

Investor Spotlight

The Pioneer of Value Investing in India: Chandrakant Sampat

By Subham Sen

"Don’t try to time the market. Invest in good quality businesses, and stay invested for the long term."

- Chandrakant Sampat

In previous editions, we have explored the investment philosophies of renowned Indian investors like Ramdeo Agarwal and Ramesh Damani. They, along with other popular ace investors like Parag Parikh, Radhakishan Damani and even Rakesh Jhunjhunwala were influenced and mentored by Chandrakant Sampat. Mr. Sampat, widely regarded as the ‘Father of Value Investing in India’ was born to an Indian Gujarati family in 1929. He began investing in the stock markets at the age of twenty-six, after quitting his family business. He was one of the first investors India saw – he generated massive returns by putting money into fundamentally strong business with the hope of growth in a company’s operations by holding them for a long period of time rather than speculatively trading securities.

Simply put, value investing is an investment strategy where you buy stocks that are trading for less than their intrinsic worth and hold them patiently until the market recognizes their true value. Moreover, Sampat’s investment strategy, objectively, can be broken down into five main points:

Put your money into a business that you have an understanding of very critically.

The company should have zero or low debt.

A stock that is available at a PE of 14 or lower (i.e. an investor should pay a maximum of ₹14 for the company to earn ₹1 in profit)

A Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) of 25% or more. ROCE is an analyst's ratio to see how good a company is at turning the money invested in its business into profits of 25% or more.

A track record of dividend yield of 4% or more (i.e. for every ₹100 invested in the stock, the company will pay ₹4 per year as a share of profit)

In the 1970s, with the advent of Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA), the government of India forced foreign multinational companies operating in India to dilute their equity shares at prices lower than the intrinsic value of the company. At this time, Sampat bought stocks of consumer driven businesses like Nestle, Gillette and Hindustan Unilever, which later turned out to be multibaggers. Long term accumulation of stocks like this and among others, Colgate and Procter & Gamble, led to him earning heavy dividends as well as appreciation on capital.

He was also a staunch proponent of the liberalization, privatisation and globalisation of the Indian economy in 1991, and had foreseen the importance of the Indian markets given the large consumer base.

His advice to all investors was to focus on one’s physical health, exercise regularly and eat healthy. He believed that would add meaning to the process of accumulation of wealth, along with helping us to make wise decisions, maintain patience and stay focused. Although we lost the legend in 2015, at the age of 86, his life and investment journey both serves as a guide for every investor and motivates us throughout.

Fundamental Analysis 101: EBITDA

By Arshia Kohli

EBITDA, or Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization, serves as a pivotal metric that delves into a company's operational performance. Essentially, it represents the earnings derived from core business operations by excluding certain non-operating expenses. To arrive at EBITDA, one starts with the operating profit and then accounts for costs related to goods and services, sales and marketing, research and development, and general and administrative expenses. Notably, EBITDA deliberately omits interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, thus providing a snapshot of a company's operational profitability.

History

The origins of EBITDA can be traced back to the leveraged buyout (LBO) boom in the 1980s. During this period, there was a significant increase in the number of corporate takeovers and buyouts facilitated by high levels of debt financing. In such transactions, buyers were often focused on a company's ability to generate cash flow to service the debt rather than its reported net income. EBITDA emerged as a useful metric in this context because it provided a quick approximation of a company's cash-generating potential from its core operations.

Advantages

1. Cross- border comparisons

When comparing companies operating across different regions, the complexity introduced by varying taxation and accounting standards can obscure the financial landscape. In this context, EBITDA emerges as a valuable solution, providing a standardized metric. This enables more straightforward cross-border comparisons by offering a common ground for evaluating companies, despite the diversity in international financial reporting standards.

2. Mergers and acquisitions transactions

CEOs leverage EBITDA to evaluate potential targets by honing in on the core profitability of the candidate company. This focused assessment aids in making well-informed decisions about acquisitions. EBITDA's contribution lies in its ability to facilitate apples-to-apples comparisons of companies' operational strength. By excluding certain non-operating expenses, such as interest, taxes, and depreciation, EBITDA provides a clear and standardized view of a target's earning potential.

Buffet’s View: Cautioning Against Over-valuation

Despite its usefulness, Warren Buffett famously remarked, "When CEOs tout EBITDA as a valuation guide, wire them up for a polygraph test." Buffet also refers to EBITDA as ‘BS’ earnings. He argues that EBITDA, which excludes interest and taxes (I and T) alongside depreciation and amortization (DA), can lead to over-valuation.

This metric offers a limited and short-term perspective on a company's earnings potential by ignoring core expenses. When talking about the ignorance of “I”, he focuses on the phrase "leverage is the ultimate two-edged sword" implies that while leverage can magnify gains, it also amplifies losses. In other words, using borrowed funds can enhance both positive and negative outcomes. Buffett acknowledges that when investments perform well, leverage can significantly boost returns, allowing investors to earn more than they would have without borrowed capital. However, on the flip side, if investments do not perform as expected, losses are also magnified, and the impact on the investor's capital can be more severe. This is something which is not taken into account using EBITDA.

To truly understand the implications of the EBITDA for a business, it is crucial to understand what it excludes, so that these factors may be taken into account during a more comprehensive analysis:

1. Depreciation

In sectors where physical assets play a significant role, depreciation can be a substantial cost. Manufacturing and heavy industries are prime examples where machinery, equipment, and infrastructure depreciate over time. The automotive industry, for instance, heavily relies on expensive manufacturing equipment, and the depreciation of these assets is a substantial cost. Similarly, in the energy sector, especially in oil and gas, significant investments are made in infrastructure and drilling equipment, and the depreciation of these assets is a notable cost for companies. Ignoring these expenses can present an incomplete and even misleading picture of a company's income.

2. Amortisation

Amortisation is often associated with intangible assets, and one sector where this is particularly relevant is the pharmaceutical industry. Companies invest heavily in research and development to develop new drugs and treatments. The resulting patents, representing valuable intellectual property, are amortized over their useful life. The amortization of pharmaceutical patents is a significant cost for companies in this sector. Similarly, in the technology industry, companies frequently amortize the costs associated with acquiring or developing intellectual property, software, or copyrights. Ignoring these expenses can present an incomplete and inflated picture of a company's income.

3. Interest Expense

The neglect of Interest Expense in EBITDA is another critical factor to consider. Industries with high levels of debt, such as steel, oil and gas, and telecom, face substantial financial burdens in the form of interest payments. Ignoring this significant expense could provide a skewed and overly positive view of a company's financial health, especially if it operates in a sector where debt plays a substantial role in financing operations. In such cases, understanding the true cost of debt is essential for a comprehensive assessment of a company's financial stability.

Indian Bond Markets – Understanding Illiquidity and Foreign Investment Concerns

By Neel Issrani

A bond is like a loan that you give to a company or government. In return, the issuer promises to repay the money you lent them (the ‘principal’), plus interest at a later date. It is a type of ‘fixed-income’ instrument as the interest you receive is fixed or benchmarked to an index. This is why, unlike a stock, a bond gives you a relatively predictable income, has little volatility and is considered a relatively safer investment.

The two major types of bonds, based on the issuer, are:

Government bonds

These are bonds issued by the Indian government and are considered very safe because the government is highly unlikely to default on its payments. Government bonds are often used to fund various government projects and initiatives.

Corporate bonds

These are issued by companies for their business activities and can offer higher returns compared to government bonds, but they also come with a higher level of risk – depending on the specific company.

Although India is the 5th largest economy in the world, it ranks 15th in the largest bond markets. India’s bond market capitalisation is more than $1.2 trillion. For comparison, India’s equity market is valued at over $3.31 trillion. Why is India’s bond market so small? And what's the way forward?

Illiquidity – Lack of a secondary bond market

A noteworthy feature of bonds is that apart from investing in them and holding onto them until maturity, they can also be traded in the secondary market. This trading in the secondary market is dramatically low for corporate bonds due to a tendency to invest and hold until maturity that the investors exhibit. Now, because of the illiquid nature of bonds in the secondary market, this deters investors from buying them in the primary market in the first place.

Limited Foreign Investor and Retail Participation

Banks are the major holders of India’s government bonds. This is because they are required to invest in government bonds to meet the Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) which is set by the RBI. So, banks have a compulsion to invest at least 18% of their deposits in government bonds.

Foreign participation in India’s bond market is around 0.9% which is lower than other countries. This is majorly due to India’s exclusion from the global bond indices which leads to very few foreign investors in the market. Also, almost all corporate bond issuances take place through the private placement route so retail investors miss out.

Restricted access to lower-rated companies

Almost 98% of the companies that have issued bonds in the Indian market are rated AA or higher. As a result, there are lots of companies that are rated below AA which do not issue bonds in the market as they would entail higher interest rates than commercial banks.

The way forward

For India to become one of the largest economies, it is important to have a large and liquid bond market. The government has been trying to include India in the global bond indexes and JPMorgan Chase & Co has announced that it would include Indian government bonds in its GBI-EM global index suite from June 2024. This is just the start and other indexes are also expected to include India's bonds in the coming years. There is also scope for regulatory change that widens India’s corporate access to overseas capital markets, something that is likely to be gradual. Although these are pivotal steps in the journey, there is still a long way to go for the Indian bond market.